Suffrage at Heart: The Women Artists of Boston’s Ward 8

Who were the women artists who claimed their right to vote in 1920s Boston?

by Laura R. Prieto

In 1915, the editors of the magazine Arts and Decoration observed that “all the women in art [seem to] hold the cause of suffrage at heart.” That same year, women artists proudly took their place among the roughly 15,000 marchers demanding the right to vote in Boston. As in other suffrage marches, they organized in groups with banners, proudly announcing their professions. We do not know their individual names, but according to the printed instructions, artists and art students lined up behind their banners on Clarendon Street, in the heart of Ward 8, waiting for tip off

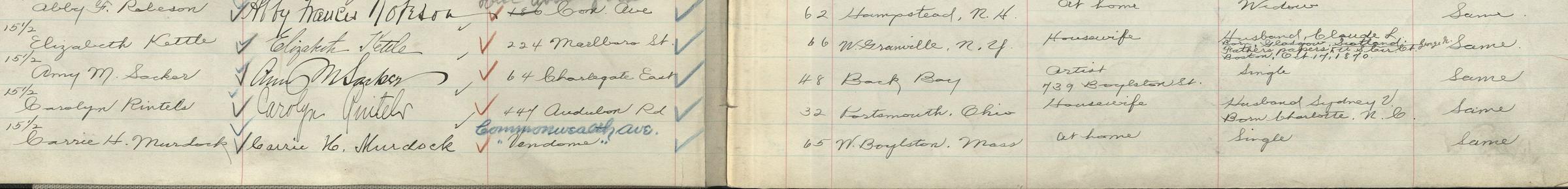

Five years later, over 50,000 Boston women lined up again – this time, to register to vote, having finally gained suffrage rights through the Nineteenth Amendment. And again, Boston’s women artists showed up. The Mary Eliza Project Team has located about twenty women artists in the registers so far, including seventeen from Ward 8, the longtime core of the city’s art scene. Five women listed their place of business as “30 Ipswich” – the address of Fenway Studios, now a National Historic Landmark and the oldest, continuously occupied artists’ space in the United States.

Also among those registering was sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd, renowned not only for her bronzes but for her work with the American Red Cross, creating facial prosthetics for World War I soldiers who had been disfigured in combat. But the city officer who registered Ladd to vote identified her occupation simply as “married.”

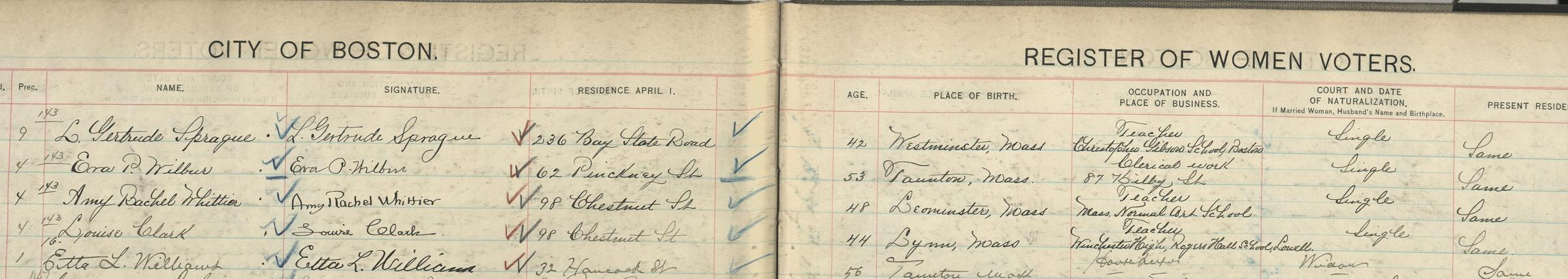

While the officials registering women to vote sometimes overlooked women’s professional accomplishments, other institutions in Boston helped women artists fulfill their ambitions. Ladd had initially come to Boston from Pennsylvania to study art at the Museum of Fine Arts School. Artists Mary B. Titcomb and Adelaide Coburne Palmer, both born in New Hampshire and newly registered voters in 1920, had studied there as well. The Boston MFA school had welcomed women since it opened in 1877. It quickly became known for providing rigorous education for those aspiring to art careers, regardless of gender. The MFA School also allowed women to serve on its governing council from 1885 on. Its alumnae distinguished themselves in many branches of art, naturally including portraiture and still life painting, which were considered more appropriately feminine than some other genres.

MFA School graduates found success in decorative arts and design too. Amy Maria Sacker, a Boston native, was a leading force in the Society of Arts and Crafts, headquartered on Newbury Street. Along with her illustration work and teaching in her own design school, she created the covers of hundreds of books, including many of Louisa May Alcott’s novels. Sacker spent 1919 as an art director in Hollywood’s early film industry but returned to Massachusetts in time to register to vote in her home city.

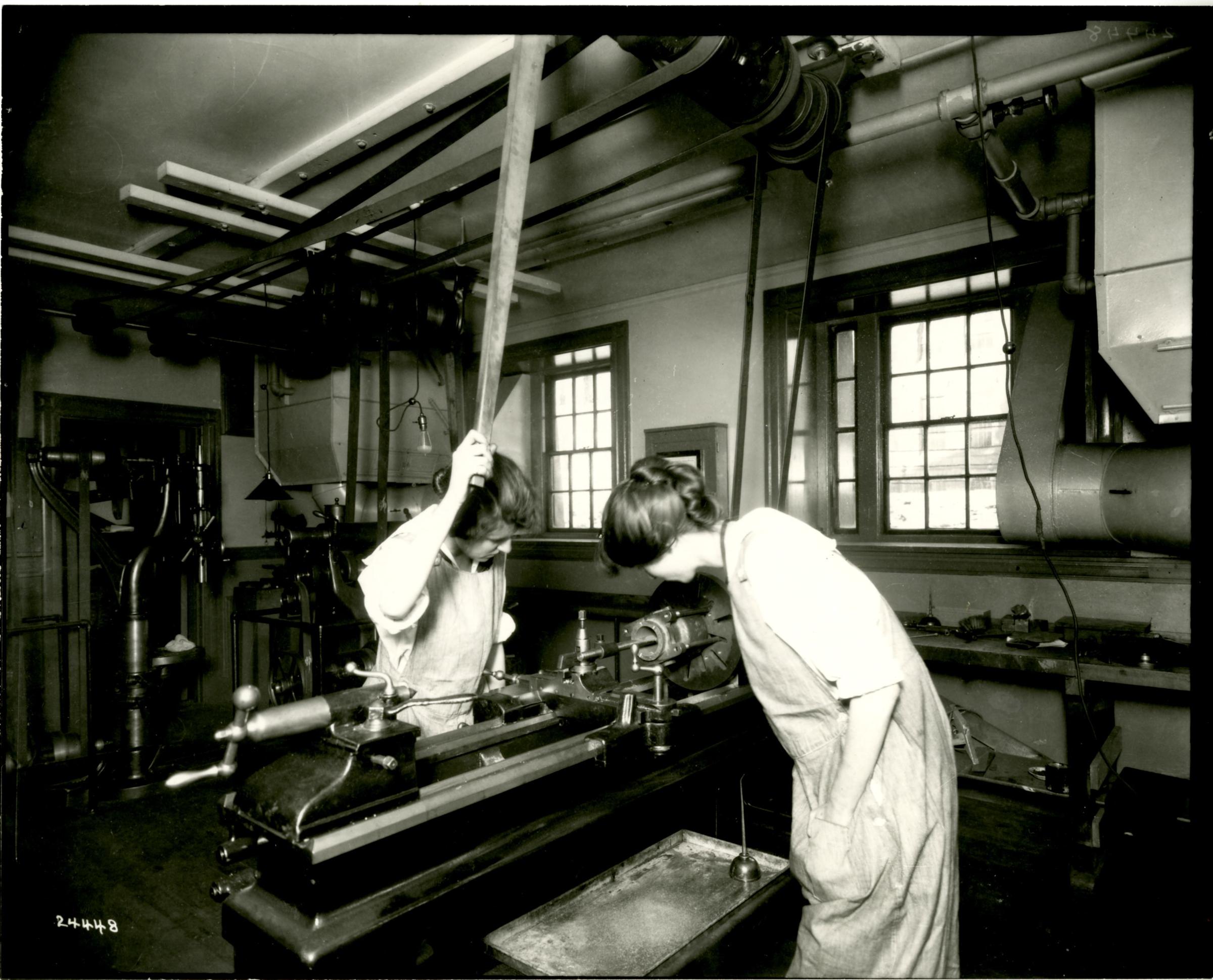

Two of Ward 8’s newly registered voters in 1920, Mary Titcomb and Margaret Foster Richardson, were alumnae of both the Boston MFA School and another of the city’s important educational institutions: the Massachusetts Normal Art School, then located at the intersection of Newbury and Exeter. State officials had created the school (now Massachusetts College of Art) in 1873 to meet a mandate for art instructors in public schools. Like the MFA school, it admitted women from the start. Classes ranged from painting and sculpture to industrial drawing and woodwork.

Newly registered voters in 1920 included women connected to the Boston Normal Art School in different ways: 22-year-old student Gladys Lynch (living at the Franklin Square House), teacher Amy Rachel Whittier, and graduates Zelpha Plaisted and the newly married Kathryn Nason Piston.

These creative professionals felt a sense of purpose and joy in their work – as Margaret Foster Richardson vividly conveys in her self-portrait, A Motion Picture (1912). Richardson depicted herself mid-step while hurrying past in her painting smock, brushes gripped in both hands. She is both a modern woman and a busy artist, beaming with self-confidence.

The Boston women who registered to vote in 1920 reported a great variety of occupations – an even longer list than the categories on the Suffrage March list – from artist to corset maker, educator to cherry picker, department store employee to trained nurse. Stay tuned for more of their stories as the Mary Eliza Project continues!

For further reading:

- Buildings of New England, “Massachusetts Normal Art School,” August 1, 2020.

- Phil Edwards, “The Facial Prosthetics of World War I: Why the war’s wounded needed a sculptor,” Vox (Nov 8, 2018).

- Erica Hirschler, A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2001.

- Massachusetts Historical Society, “A Rash and Dreadful Act for a Woman,” July 2010.

- Laura R. Prieto, At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Mary Eliza Project Page

Dr. Laura R. Prieto is a professor of History and Women's and Gender Studies and the Alumni Chair of Public Humanities at Simmons University in Boston. You can follow her at LauraRPrieto.com.