And Hijinks Ensued

In 1873, Boston women couldn't vote in local, state or federal elections. But could they run for office? Some women decided to find out. Hijinks ensued.

By Marta Crilly

In November of 1873, Lucretia Crocker, Abby W. May, Lucia Peabody and Ann Adeline Badger won seats on Boston's School Committee. While the election results and vote tally seemed straightforward enough, there was one complicating factor - their gender. In 1873, Boston women were barred from voting in local, state, and federal elections. The law did not, however, explicitly state that women couldn't run for office, only that they couldn't cast ballots. In fact, in some other Massachusetts towns, women could and did run for and win elected School Committee positions, even though they couldn't vote themselves.

So, a group of Boston women decided to test the system and ran campaigns for the Boston School Committee. Four of them, Lucretia Crocker, Lucia Peabody, Abby W. May, and Ann Adeline Badger won their races, elected by an all male voter base. All four women were ideal candidates for the School Committee. Shortly after they won their respective races, a Boston Globe article published on December 11, 1873, commented, "It is quite certain that no one will say that the four women who have been chosen to the office are not well fitted at least so far as education attainments are concerned." Lucretia Crocker had served for years as a faculty member at Antioch College, Abby May spearheaded educational and sanitation efforts in the city's West End, Ann Badger and Lucia Peabody had years of teaching experience and were school principals. Several of the women were also deeply involved in the women's advancement movement; the Globe article observed that Lucia Peabody in particular took "a radical stand" in all matters involving women's advancement.

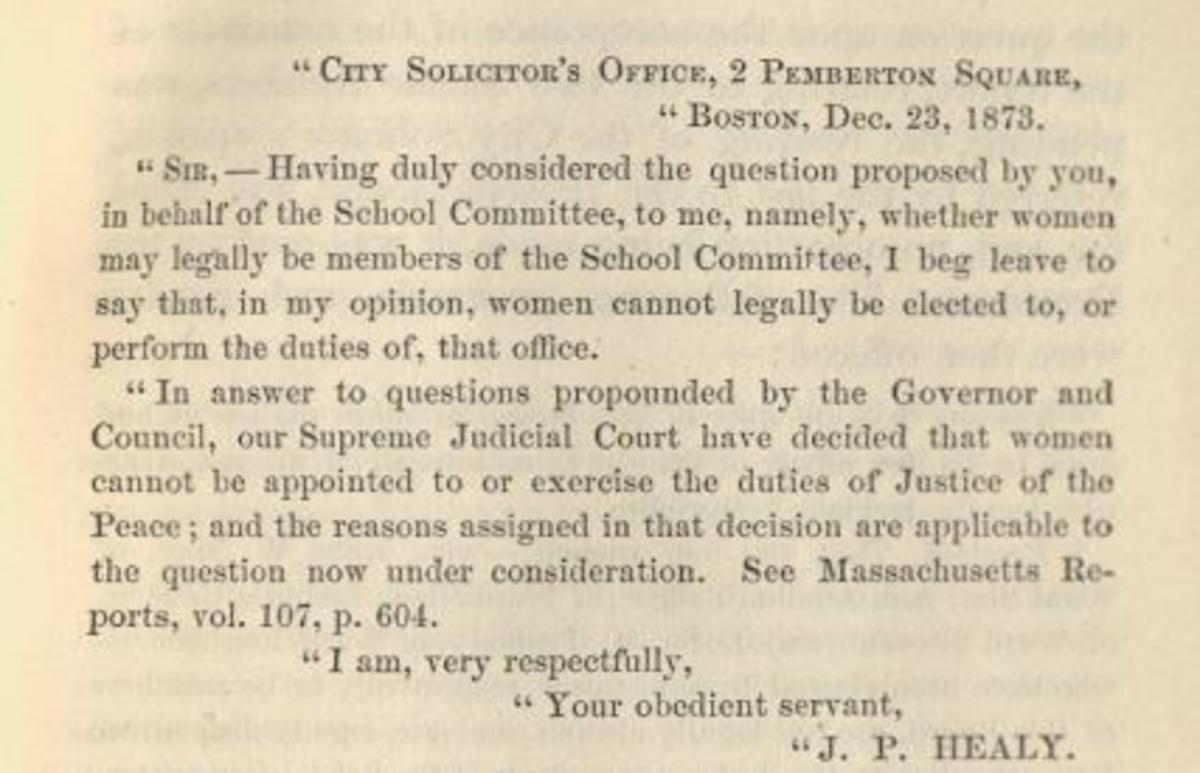

Typically, the School Committee would swear in new members shortly after the election. But as the swearing in approached, the Committee became nervous about the legality of having women serve on the School Committee, even though they had clearly won their seats . On December 10 1873, School Committee asked John P. Healey, the City Solicitor to provide a legal opinion regarding whether women could serve as members of the School Committee.

On December 23, the City Solicitor wrote a letter in which he stated that women could not legally be elected to or perform the duties of School Committee members. He based his opinion on a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Decision stating that women could not exercise the duties of the Justice of the Peace.

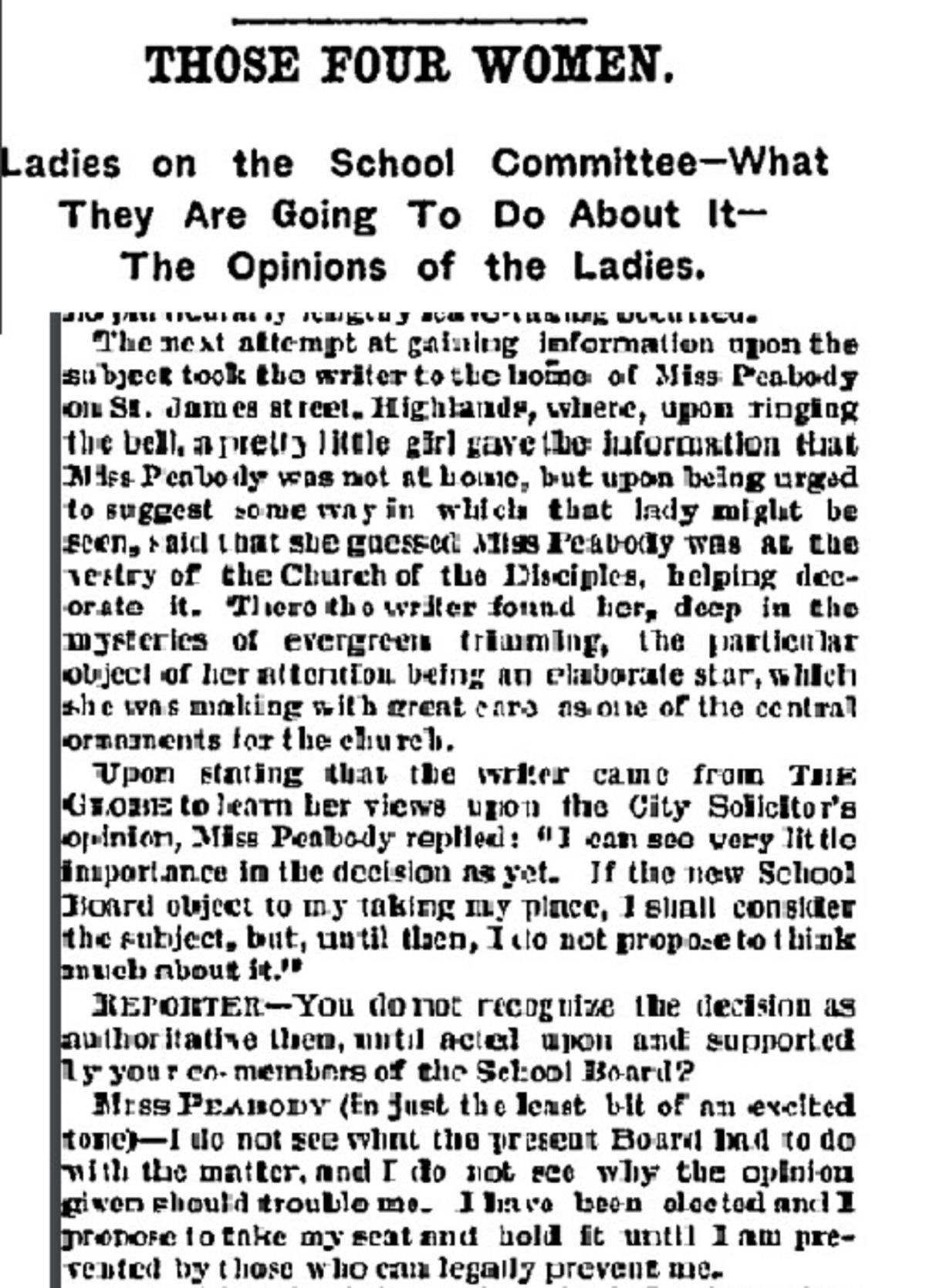

The elected women were undeterred. When a Globe reporter tracked down Lucia Peabody to interview for an article he entitled, "Those Four Women," he asked her if she was concerned by the City Solicitor's opinion. She responded, "I do not see what the present board has to do with the matter and I do not see why the opinion given should trouble me. I have been elected and I propose to take my seat and hold it until I am prevented by those who can legally prevent me."

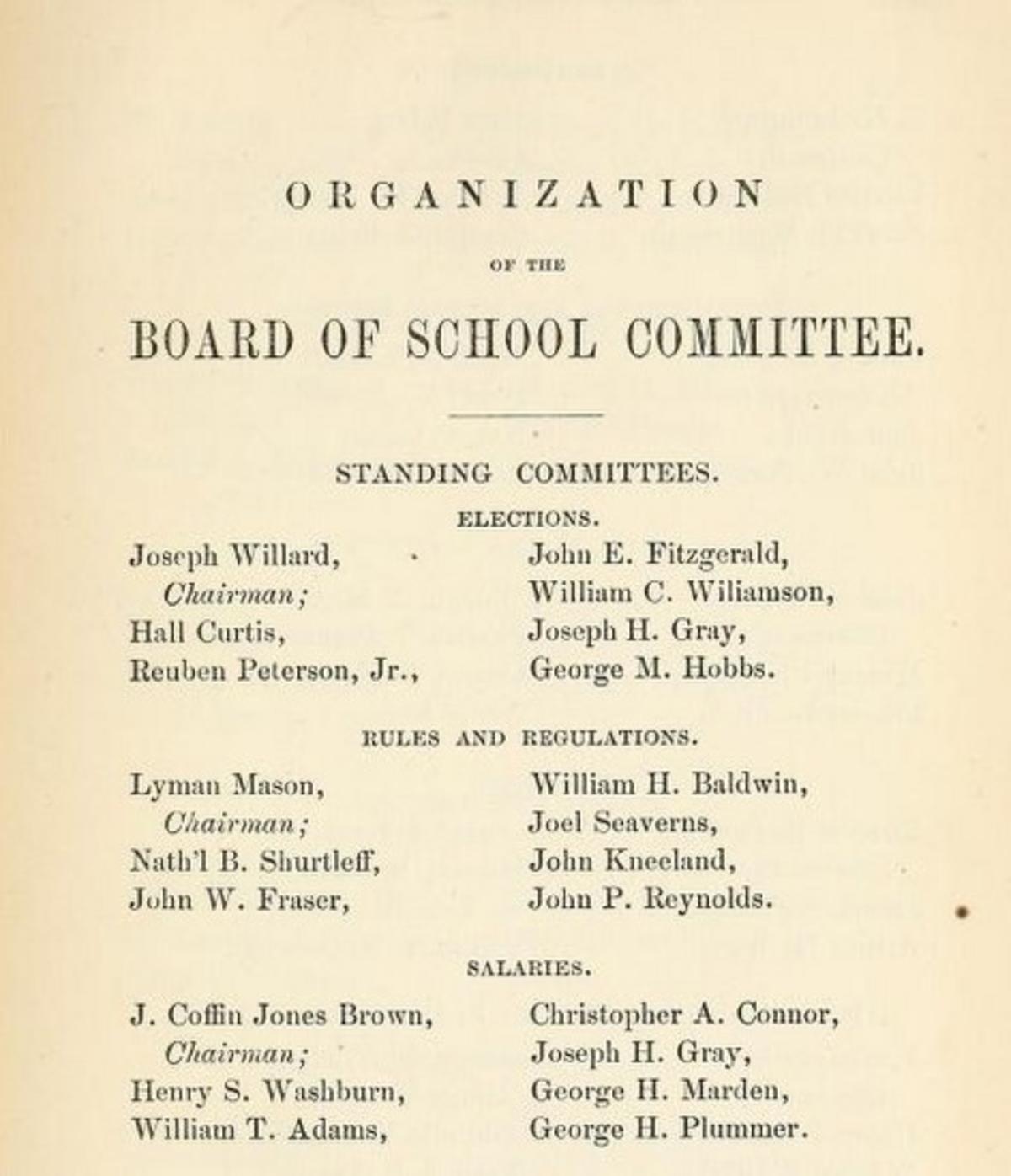

Accordingly, on January 12, 1874, Abby May and Lucretia Peabody came to the School Committee's organization meeting, with their certificates of election in hand and petitioned to be admitted to the School Committee. The Committee did not accept May or Peabody's certificates of election, but they weren't willing to outright deny them admittance to the Committee either. Rather, they decided to refer the question of having women serve on the School Committee to the Committee's Subcommittee on Elections.

The Subcommittee on Elections decided in favor of May and Peabody, openly rejecting the John Healy's opinion that women could not serve on the School Committee. On January 27, 1874, Subcommittee on Elections reported that the City Solicitor’s opinion was “not controlling” on the action of the Committee. The Subcommittee on Elections stated their opinion that women could be elected to the School Committee.

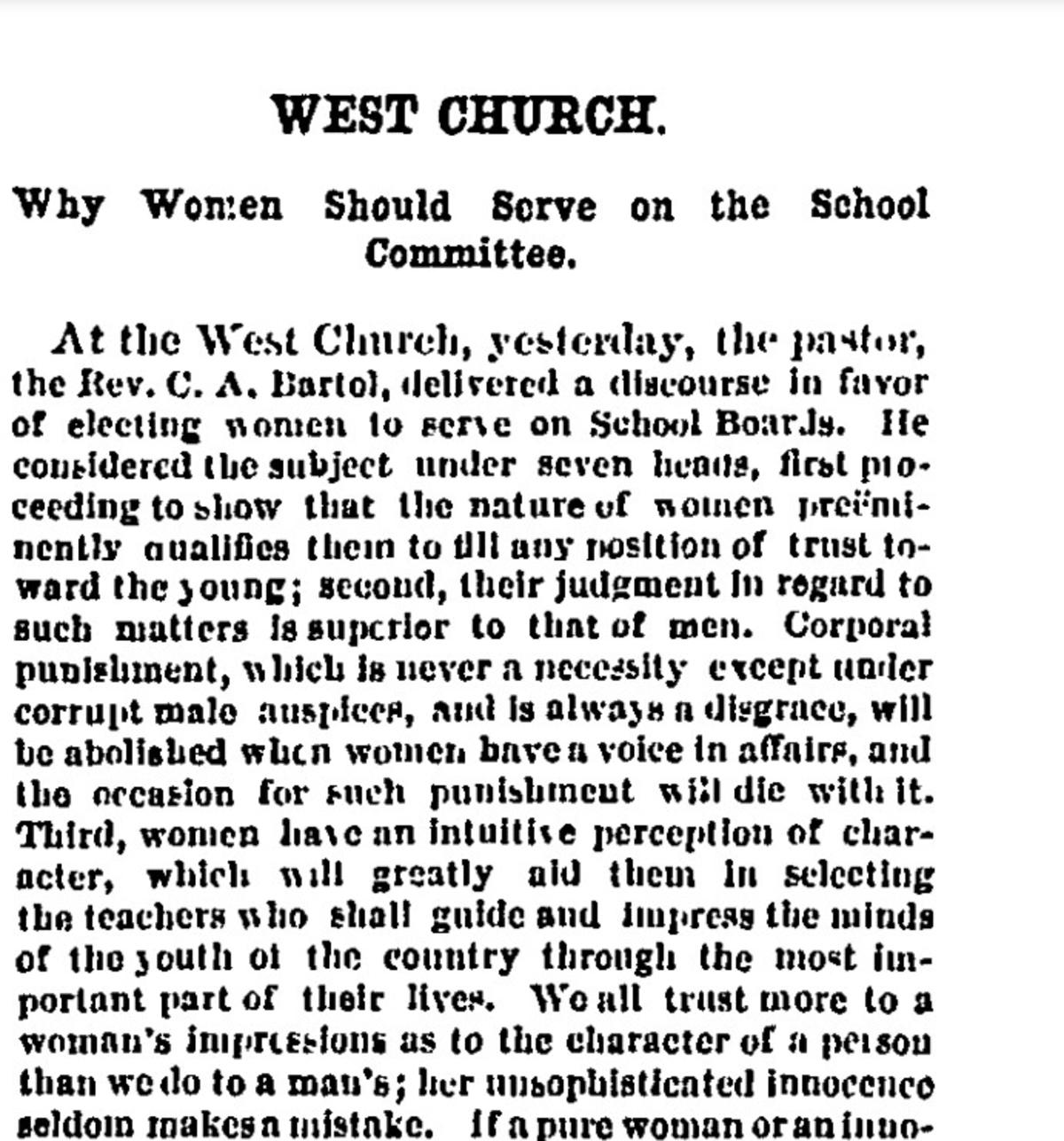

The January 27 meeting ended with the Subcommittee on Elections at an impasse with the City Solicitors, triggering a "general public uproar" after the meeting. The School Committee's annual report documents that two “indignation meetings” were held at which Bostonians protested against the exclusion of women from the School Committee.The Boston Globe reported that at least one pastor, A.C. Bartol of West Church, gave a sermon advocating for the elected women to be admitted to the School Committee. Bartol's sermon argued that women were uniquely suited to make decisions regarding the education and upbringing of children, a common refrain of the late 1800s that was often leveraged by school suffrage advocates.

As the public debated and protested, the School Committee took up the question of installing the elected women again on February 10. A number of committee members wanted to install the women, but were still nervous about breaking the law and wanted legal protection. Their solution to this conundrum was to vote against the women serving, despite their belief that the women should serve. They expected that by voting against the women serving on the committee, the question would go to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, which they assumed would rule in favor of Peabody and May. Then, they could install Peabody and May without any concerns of getting themselves in legal trouble.

As the School Committee expected, on February 16, the Massachusetts House of Representatives, likely triggered by the complaints of exasperated and angry constituents, asked the Supreme Judicial Court, “Under the Constitution of the Commonwealth, can a woman be a member of the School Committee?" And as many members of the School Committee had hoped, the Supreme Judicial Court responded that the State Constitution said nothing about School Committee membership; thus the women were not constitutionally barred from serving on the School Committee.

Thinking their problem was solved and their legal derrieres covered, the School Committee again asked for the City Solicitor's opinion on the legality of women School Committee members. Steadfast in his aversion towards women serving on the committee, John Healy firmly responded that his opinion had not changed. He stated that he had based his opinion on state statute and not on a constitutional barrier. The Court's opinion that the State Constitution didn't bar women from serving on the School Committee was simply irrelevant. His opinion stood. The women could not be admitted to the School Committee.

The School Committee took the position that, given the City Solicitor's opinion, only a court order could admit the elected women to the Committee. Accordingly, on March 24, Lucia Peabody and others petitioned the Supreme Judicial Court to make a decision regarding the petition to admit women to the School Committee. If the Committee required a court order, Lucia Peabody would endeavor to obtain one. To the surprise of many, including the School Committee, the Supreme Judicial Court dismissed her petition and batted the matter back to the School Committee. The Court stated that while admitting women to the School Committee wasn't unconstitutional, neither was Peabody or May entitled to a seat. In other words, the Court said that the School Committee had the right to decide whether or not they wanted to admit women. They weren’t prohibited from admitting them; but neither were they required to do so.

The School Committee’s report states that the SJC decision was “a surprise to members of the Board and to the people generally.” The expectation had been that the Court would instruct the School Committee to admit the elected women.

Again, the public protested, and in response the Massachusetts State Legislature passed an act declaring women eligible to serve as members of local school committees. Women could be elected to the Boston School Committee, even if they could not vote in School Committee elections.

As soon as the law passed, more women ran for the Boston School Committee, and again an all male voting body elected them. In 1875, six women are listed as members of the School Committee. Lucretia Peabody Hale, Abby W. May, Katharine G. Wells, Lucretia Crocker, Lucia Peabody, and Mary Blake. Four years later, in April of 1879, the Massachusetts State Legislature passed an act to enable women to vote for school board members.

The fight for women to be elected to the Boston's School Committee is a complicated legal and bureaucratic saga, but throughout the story, we see Bostonians making their political wills known and effecting change. The saga began with an all male voting body electing women to the School Committee and ended when public advocacy resulted in legislative change. Advocates for women on the School Committee attended School Committee meetings, organized "indignation meetings," preached sermons, petitioned the courts, and prodded legislators to act.

Though Boston suffragists would not be victorious in their fight for full suffrage for over 45 more years, their 1874 efforts and victory signaled momentum. Five years after the legislature decided that women could be elected to school committee positions, women gained the right to vote in school committee elections. The women running for office could now vote for themselves. Forty-one years later, in 1920, over 50,000 Boston women would register to vote in their first United States Presidential election. After 1920, suffrage advocates continued to fight to secure voting rights for Asian, Indigenous, and Black women who were either prohibited from voting or who faced significant obstacles when attempting to exercise their voting rights.

The Boston City Archives holds the registers of women voters starting in 1884, when women could only vote in School Committee Elections, and ending in 1920, when the 19th Amendment declared that voting rights should not be abridged "on account of sex." The Mary Eliza Project is transforming these registers into a searchable, sortable dataset. Learn more about the Mary Eliza Project, read stories of suffrage, and access the dataset for yourself!

Further Reading:

- Boston School Committee Report, 1874

- Memoirs of Lucretia Crocker and Abby W. May, prepared by Ednah Dow Cheney for Private Circulation at the Request of the Massachusetts School Suffrage Association, 1893

Marta Crilly is the Archivist for Reference and Outreach at the Boston City Archives.